Opal-

there is no precious stone in the world that catches the eye the way these

stones that Shakespeare called the ‘Queen of Gems’ do.

On a continent known for

its mineral wealth, Australia’s national gemstone it seems is not a mineral at

all as it has few of the characteristics true minerals possess (such as a

uniform crystalline structure). Instead Opal is considered a mineraloid, and for

dinosaur fans it could be argued it’s the gemstone that could represent the

Mesozoic.

Opal

requires very specific geological conditions to form and Australia produces

over 95% of the world's opal because in the Late Cretaceous the middle of the

continent sat under a warm, shallow ocean.

The Eromanga Sea lasted for around

80 million years and produced fine sand rich with silica- a strange substance

that can be considered a mineral, but also is produced synthetically and

biologically. This silica rich water seeped deep underground (helping form the

Great Artesian Basin) and filled any void and coated any fossil it

encountered. This silica then took several million years to harden and form opal.

This

isn’t the only way opal forms, only the most common. Sometimes bacteria slowly dissolved away biological material such as leaves and shells and

left behind silica in the exact shape as the original material.

Because

the Eromanga Sea covered such a large distance, the opal it would eventually

produce is as diverse as the locations where it can be found. In the flat, hot

South Australian town of Coober Pedy (where the vast majority of opal is mined)

most of these stones are considered ‘light’ opal and the fossils found here are

almost all marine. Lightning Ridge in NSW is not only the birthplace of Mr.

Crocodile Dundee himself, Paul Hogan, but the most fantastic ‘Black’ opal. Its

fossils seem to suggest the region was a forest with large rivers running down

to the inland sea. Queensland has not only the most productive dinosaur fossil fields in

Australia, but also produces ‘boulder’ opal. Both marine and terrestrial fossils

are found in this location, indicating this part of Queensland might have once

been a series of islands

In

Australia it’s possible to see great examples of all three types, along with a

number of fantastic opalised fossils at the National Opal Collection. This has

two localities, one in Melbourne (which I visited years ago) and the second in

Sydney. Both have free entry and are attached to a large opal showroom where

visitors can purchase their own gemstone to take home.

Though

not the largest museums in the world, they are well presented with both

life-like models of dinosaurs, pterosaurs and the world’s most famous opalised

fossil, Steropodon. These are great to see, but in this museum it’s all about

the opals, and Sydney’s National Opal Museum has plenty to see.

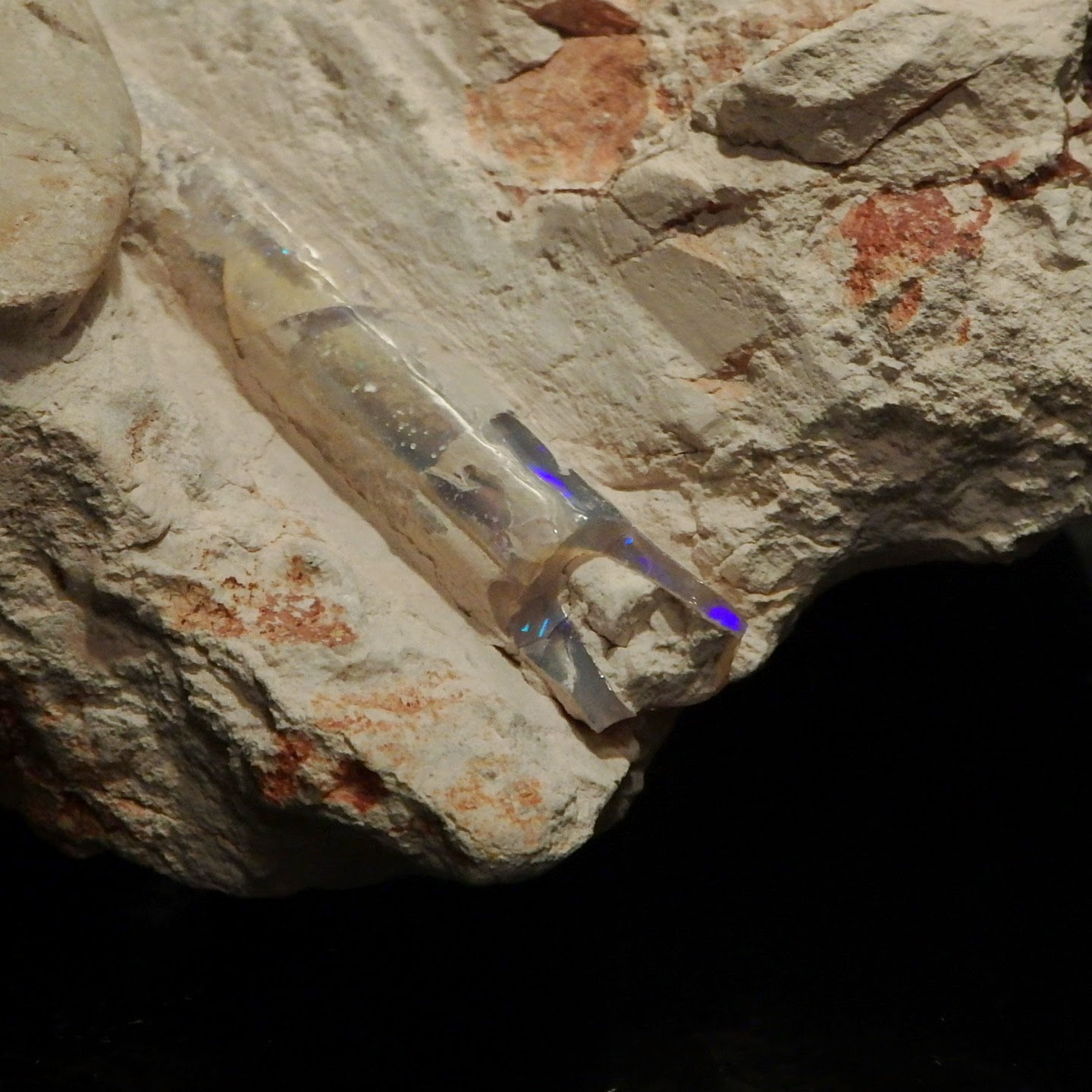

There are the usual opal shells, a few starfish

and the long, tooth-like inner guards from the extinct cephalopods called

belemnites. The museum also has a large number of turtle fossils, along with

crocodile scales and the teeth of large lungfish, all opalised.

The

most famous fossil on display is ‘Nessie’, a near complete juvenile plesiosaur

(possibly a pliosaur) found at Andamooka, South Australia, in 1968 and has been

placed under Australia’s National Heritage Laws. 50% of Nessie’s fossils have

opalised, and in the marine reptiles stomach were discovered gastroliths,

belemnite guards and fish bones- many of which had opalised too.

Though

far from complete, the museum hosts a large number of opalised dinosaur fossils

as well. Amongst the ribs, vertebra and a possible dinosaur claw are a number

of large theropod teeth. These were from a medium size carnivore, though due to

the nature of the opalisation these fossils do not contain many details to let us work out exactly what sort of theropod they came from.

Though

far from the only museum hosting opalised fossils (Bathurst, the National

Dinosaur Museum and the South Australian

Museum has opals on display), Australia’s National Opal Collection contains a number of great

specimens and well worth a look.