The Royal

Ontario Museum (ROM) was the main reason I wanted to visit eastern Canada, and

I had intended to drop in on Friday afternoon when it would be reasonably quiet.

Instead I ended up going Saturday morning. Unfortunately this particular

weekend Toronto was hosting its Santa Parade, one of the largest Christmas

parades in the world, so you can imagine how large the crowds were during my visit.

It also didn’t help that the museum was displaying the Dead Sea Scrolls as well

at the time.

Always keen to try the public transport of a city I caught the Toronto subway system, which I have to say is easy to use. Working out how to catch a train or bus can sometimes be a pain in a foreign country as you’ll usually find yourself staring at some automated kiosk that requires a bachelor’s degree in astrophysics with a minor in international diplomacy to figure out how to obtain a single daily pass ticket. Toronto has kept it easy for the infrequent traveller as, just before the subway turnstile there’s a little ‘bubble-gum machine’ that takes change (something you always end up accruing and have trouble getting rid of in a foreign country) and spits out tokens. The added bonus is you get to use a subway token- how ‘quaint’ is that?

The ROM has its own station on the network and oh what a station it is. Much like the American Natural History Museum in New York, the platform has been ‘themed’, with all of the columns holding up the tunnel roof turned into Mayan, Egyptian and Native American totems and statues.

The museum

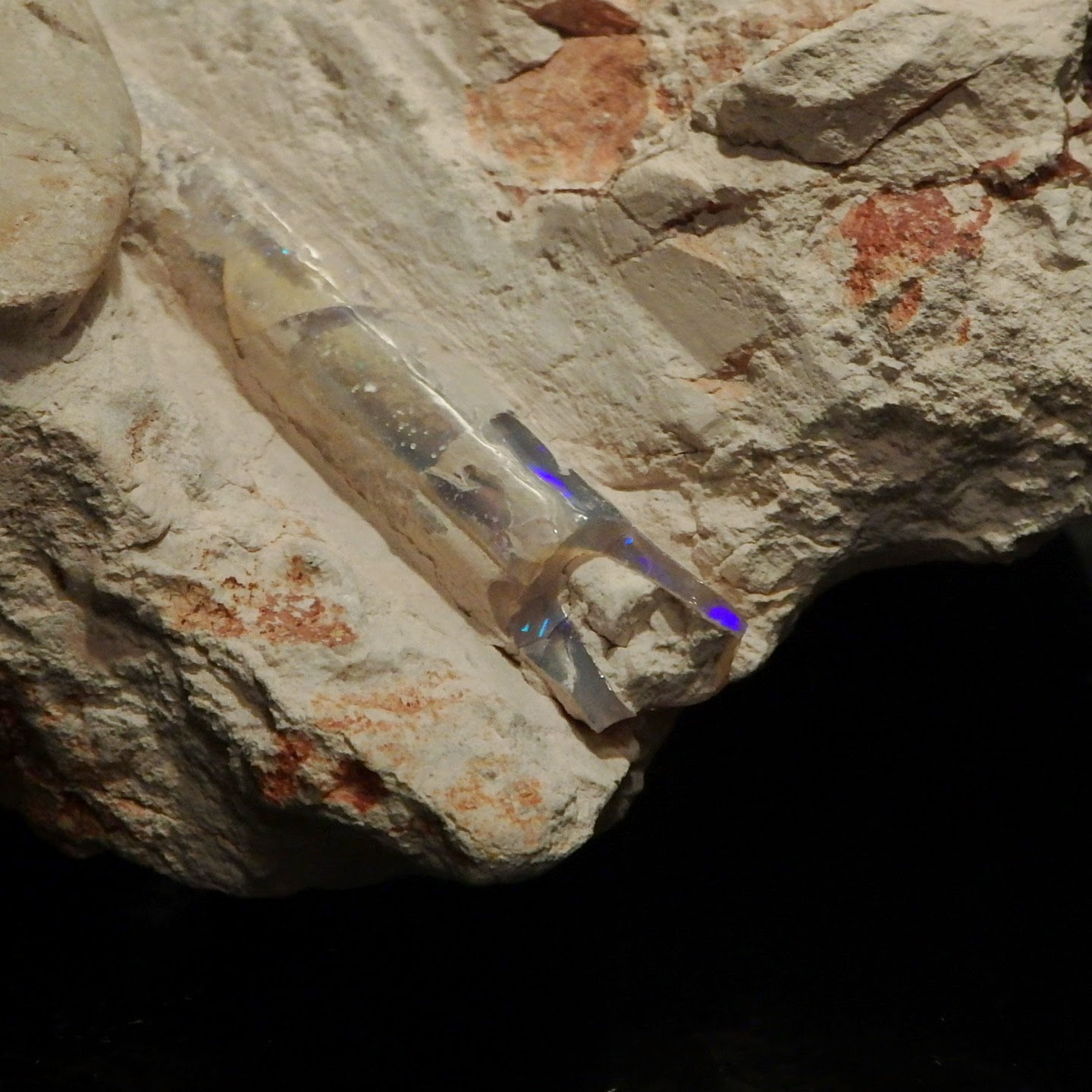

itself is a little odd as the older building has recently had a bizarre

extension added to expand the original floor space. Called the Michael Lee-Chin

Crystal, the building now looks like it has one of those old Rubik’s cube

snakes bundled up in the middle of it. This extension is all odd angles and

weird protrusions jutting out in the strangest places and I don’t mind it per

say, but it must be a nightmare to work in as you’d be in constant fear of

smacking your head or shin if your mind wanders off for even a second.

I wasn’t all that interested in the Dead Sea

Scrolls but did have a quick look. As you can imagine there wasn’t a lot to see

as the light levels have to be low to save the ancient parchment, and each

little display was behind some very thick safety glass and surrounded by about

a thousand onlookers. This was definitely not a display to see with a large

crowd. What I did find fascinating was that the museum rotated the scrolls on

display every few weeks, I guess ensuring those Dead Sea Scroll groupies out

there get a chance to see their favourite proverb or ancient Hebrew shopping

list at some point.

Because the ROM

is basically now a building inside another building it can get a little

confusing, so my advice is make sure you grab a map (it has 6 pages, so that alone

should tell you things can get a little confusing inside), and to quote one of

my favourite horror movies, ‘stay on the path’.

Things are set

up that you have to go through some galleries to get to others so there isn’t

any sort of central corridor that I could see. This means make sure you’ve got plenty

of time as I don’t think this is a museum where you can skip in, see the

dinosaurs, and skip out again.

First you’d have

to find them, and this actually took me a few goes as the prehistoric gallery is

through a weird little corridor that, at the time, held a kiddies colouring in

station and a small room full of bird display cases. If I didn’t have the map I

doubt I’d have ever investigated the area beyond this point and may have missed

the dinosaurs all together.

So…through the

room, around the Australian bird display, turn the corner, down the ramp and

you’re now in the first of three prehistoric galleries containing the ROM’s

mammal and Cretaceous displays.

Here you’ll see

some museum staples like an Irish elk

(which I think every museum I’ve visited in the last 3 years has had) as well

as a Mastodon, Giant Sloth, Short Face Bear

and Phorusrhacos.

Each Cenozoic

era seems to be represented by a little island-of-a-display that you can walk

around and view from all four sides. With the largest animals in the middle and

smaller species on the outside, this method allows for more specimens to be shown

then you’d get with just a flat display along a wall. The negative is it makes

the actually viewing of each animal hard as there’s almost always going to be

something in the way of what you’re looking at.

For the general public this

isn’t such a big deal, but for paleo-fans, well it’s impossible to get that isolated

photo of an animal without something else’s hoof, horn or tail getting in the

way. I found myself working pretty hard to get any sort of descent photo of

individual animals, and any group photo quickly merged into a jumble of brown

bones and glass reflections.

As for the dinosaur

displays in the James and Louise Temerty Galleries, well this may sound weird

but I found myself feeling a little sorry for the museum here.

They had a grand

T-rex, a charging bull-like Chasmosaurus, a few ceratopsian

skulls and a Protoceratops, but I found myself wanting something new. I

mean if you go to any natural history museum in the world you’re going to

see most of these species. For all the richness of the Canadian dinosaur fields

they’ve unfortunately exported so many of their iconic dinosaurs to the world that

most native species have now become a little old hat. This feeling certainly isn’t

helped by the fact that there doesn’t seem to be a lot of patriotism involved

with the display either. I never really found myself looking at anything that

was displayed as ‘local’; the fossils were just displayed and you were left to

work it out for yourself… but I’ll talk more about this later.

My growing disappointment wasn’t helped by two things. The first was that, as I’d been so focused on looking and photographing the animal displays I never really gave the blank Rubik’s wall behind me a close look. All those angles and protruding triangle walls meant I’d missed the tiny, almost hidden corridor from the Cretaceous display into the Jurassic, and I honestly almost walked away at that point shaking my head thinking ‘is that’s it?’

As it turns out

it wasn’t.

The Jurassic

room through that little cubby-hole (and across a weird walkway) is stuffed

with dinosaurs, including a 27m Barosaurus, Allosaurus, Stegosaurus,

numerous hadrosaurs, ichthyosaurs, an Albertosaurus, one huge Acheron

stuck hanging in mid-air in one corner, and one of those new oviraptorids

called Chirostenotes.

I know, I know,

much like Jurassic Park, many of the species I just mentioned were in fact Cretaceous.

Due to the way the display is currently set up

I think its organisers have at some stage made a really big boo-boo and are

currently trying to figure out how to fix it. To me the second gallery was

supposed to hold all the dinosaurs, while the first was supposed to be just

mammals, but when they reorganised the museum they realised they couldn’t fit

all those dinosaurs in the one room so they were forced to compromise. Again,

no real proof of this, its just that’s what it feels like and could explain the

jumbled way the dinosaurs are displayed.

Further evidence

of this is that this new gallery is huge, yet for the most bizarre reason the

exhibition’s planners have decided the best place to put their dinosaurs is

next to or behind the roof’s support columns. There’s ample free floor space,

yet everywhere you look a column seems to get in the way, and the reason I found

this so frustrating is that there just isn’t that many columns in the room to

begin with. Surely the fossils could have been arranged in a way that gives you

an uncluttered look at them?

On the far side

of the Jurassic display is the Triassic gallery; well that’s just a white

walled corridor with bare floorboards next to the toilets. There’s very little

colour throughout the three prehistoric galleries to begin with and, with so

much to show, that’s kind of understandable. Yet in this little corner where there

isn’t that much on display you’d think the ROM could really have designed a

display full of colour and life. Instead it’s a featureless alcove that hardly

anybody enters unless they’re dragging a waddling child by the hand that’s desperate

for a pee.

Having done a

little research, later I discovered the ROM’s prehistoric galleries used to be full

of murals, placing many of the skeletons in more life-like settings. They

looked fantastic in the few pictures I’ve managed to find, and this goes back

to one of my earlier points. This type of display really allows you to tell a

story, not only of the animal but where they came from. By placing them in an

environment you get to talk about that environment and can wave a little

patriotic flag at the same time (i.e. this is what Canada used to look like).

I’m not sure what it is, but many museums seem

to be moving away from this more realistic style of display into the more open,

window filled galleries you can see at the ROM and AMNH, and I personally think

it’s a mistake. Cold displays of naked skeletons that become mashed together

with whatever other fossils are nearby is certainly not an attractive way to

look at something that should be instilling the spectator with jaw-dropping

awesomeness. There’s little or no context with an open display like the ROM’s…

and as for this need for modern curators to have natural history displays in

rooms full of windows…STOP IT!

With the sun beating through glass (that’s all

too often dirty on the outside), the display becomes little more than washed-out

black and white skeletons in a room that’s stinking hot during summer and freezing

cold during winter. In the ROM, thanks to all those angled windows, there

literally wasn’t a single display case that didn’t have a dirty big, sun-filled

window reflected in it…and due to the angles of all those weird windows this

isn’t a problem that will go away as the sun moves throughout the day.

Brick up those

windows, splash some paint on those walls and let’s get back to the way we used

to present our dinosaurs shall we?

As for the rest

of the ROM, well it seems to be a cross between a natural history museum and

the New York MET. The remaining galleries were mostly human cultural displays

from around the world.

There’s a great ancient Egypt

I may be a little unfair here but the ROM also has potentially

the worst museum gift shop I’ve been to in my life. I mean, there wasn’t a

single dinosaur book for anyone with a reading level past a kindergartener (I

can only hope I perhaps missed another museum store in the kaleidoscope

building).

Also keep an eye

out for a number of other fossils hidden throughout the building. Soaring high

above through one roof space is a skeleton of Quetzalcoatlus, while one wall in the main entry hall had a large hadrosaur.

There may be others, so watch out for them.

Still, despite my misgivings about the building, the ROM has one of palaeontology’s largest exhibits of prehistoric creatures…if only they were given a little bit of character it would easily rank as one of the world’s greatest displays!